The spicules act like an internal skeleton, giving the sponges shape and support. They come in a beautiful range of shapes: spines, grappling hooks, jacks, pollen-like spheres, and coralline branches. In fact, they can be sturdy and tough, because their jelly-like middle is often full of microscopic pieces of hard minerals, known as spicules. With such simple body plans, you might expect sponges to be flaccid and soft. And their bodies comprise just two layers of cells, sandwiching a jelly-like filling. They have no symmetry-no left or right, no front or back. They have no nervous, digestive, or circulatory systems. It’s also unclear exactly what the mucus is or how it’s moving backward through pores.Sponges are animals that do incredible impressions of inanimate objects. But biologists need to dig deeper to figure out how widespread the mechanism is. archeri that uses the counterflow technique, Leys says. The team also noted a similar behavior in an Indo-Pacific sponge ( Chelonaplysilla sp).

Most sponges appear to sneeze, so it’s likely not just A. “They let the animals show for themselves what was happening.” “There’s so much to be said for a study that really spends time and watches,” Kahn says.

Scientists view sponges primarily as habitat builders, but the mucus buffet shows they also perform an important function as food providers, says Amanda Kahn, a marine biologist at Moss Landing Marine Labs in California who was not involved with this work. Other sea critters feast on these ocean boogers, like brittle stars and small crustaceans. In real time, this sponge takes between 20 and 50 minutes to complete a sneeze. As the time-lapse video zooms in closer, it’s possible to see tiny specks of debris floating out of these pores and traveling along a “mucus highway” where they collect into stringy clumps of goo floating above the surface of the sponge.

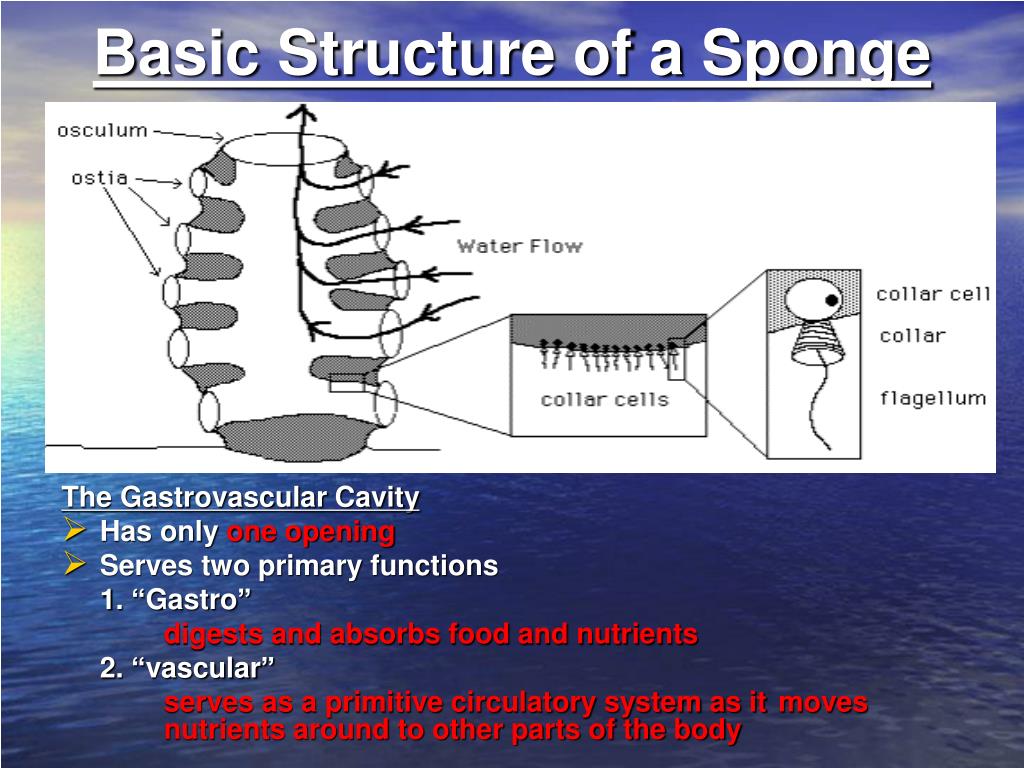

The Caribbean tube sponge ( Aplysina archeri) uses contractions - called “sneezes” - to help eject mucus from its pores, or ostia.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)